Please pick three…

Back in December, I realised that for the structure of the HayleyWorld app to work as I envisaged, I needed to rethink the number of topics for readers to select. Asking readers to select three topics of "conversation" with William Hayley at a time has always felt – and still feels – appropriate: picking one or two at at time would mean too many interruptions, while selecting more than three felt like asking for too much.Not a scientific approach, it's true, but sometimes it's worth listening to a gut reaction in the first instance… and then pivoting if, in user testing, you discover you've got it wrong.

Then my development partner Michael Kowalski mentioned that reaching the end of each topic and going straight on to the next one felt disorientating. He suggested contextual essays at the end of each topic.

I'd always planned to write a contextual essay on each major topic, but… not until much later in the process. Realising that I'd need at least two or three of these in time for user testing rather focused my mind. And changed it.

|

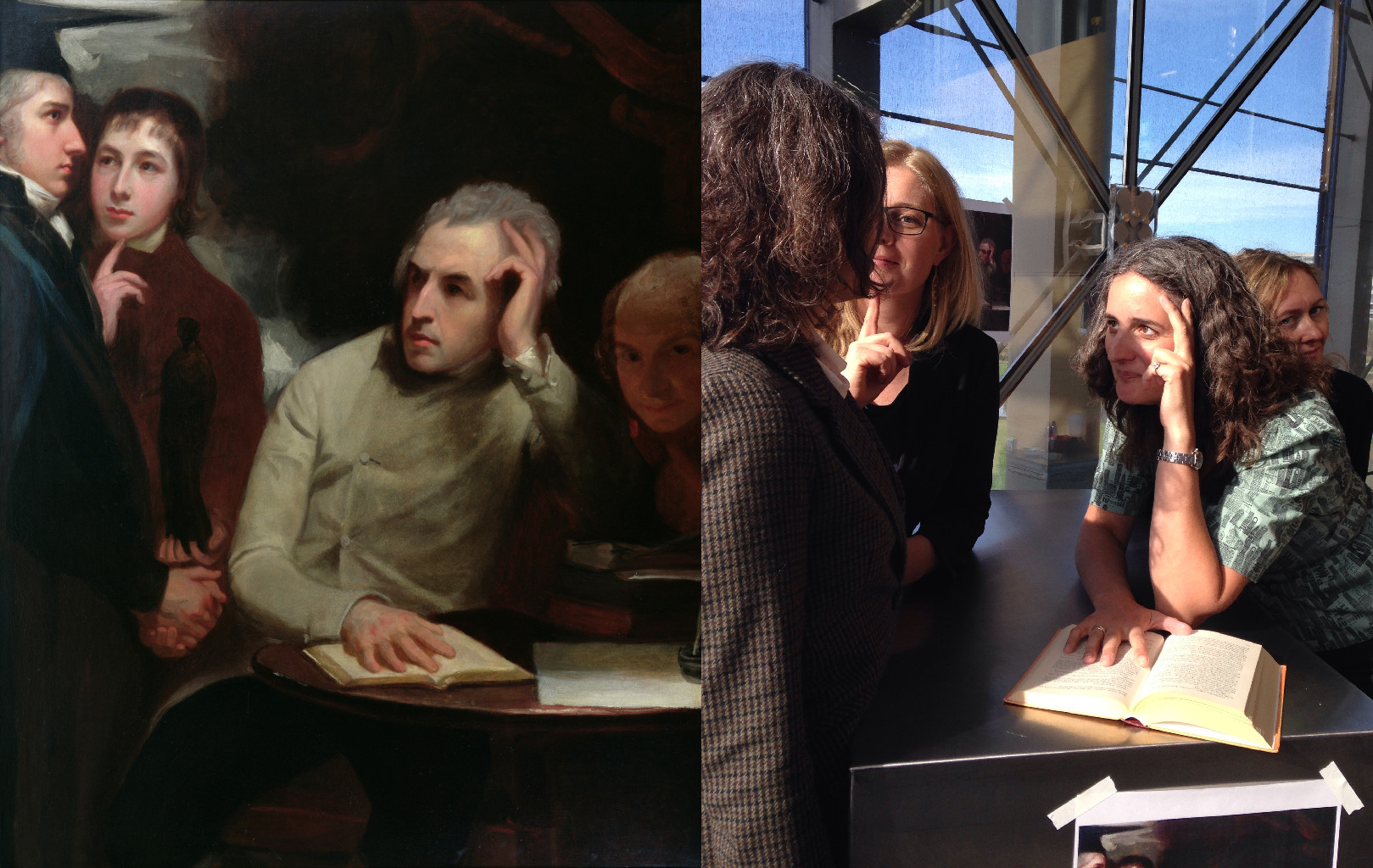

| Recreate George Romney's Four Friends pic with Vangoyourself |

Essays or documentaries?

Short, video documentaries, I realised, would probably be more appropriate. They- would better exploit the capabilities of digital tech

- could ensure that a reader's "relationship" with me-as-biographer would be different in kind and quality than their relationship with Hayley (I want that to feel closer, more direct), and could act to deepen the latter

- can contextualise more effectively, by taking readers to where stories actually happened

- provide the opportunity for me to include a variety of voices and perspectives

- (this was a major factor), because I edit video professionally, it feels like they'd be quicker and easier to construct than a well-written essay would be. I could be wrong there, though.

Pick three, three times

Meanwhile, I also decided to restrict the number of topics/chapters to nine. However, when I sat down* to do it, I couldn't squeeze all the material in. So there'll be twelve, which means readers will choose three topics, three times during the zoeography (with the last, unchosen three either delivered at the end, or not, as readers decide).Once I'd done this, I needed to trawl through all 440-odd "pages", checking and amending keywords, to ensure that the right material appears in the right chapter(s): some content is relevant to more than one topic, so will appear in the first pertinent one the reader chooses.

Setting the tone

Then I needed to render the topic/chapter titles into authentically Hayleyan language. This demanded more trawling through material to find appropriate wording, and a lot more sitting down thinking*.Got there in the end, though, and the topics/chapters will be (in no particular order, for obvious reasons)…

Marriage & love

Parental duties, children & education

Physic

Death & dying

Sensibility & instances of friendship

Popular applause & emolument

The theatre

Mental infelicities

Religious & political topics

Literary occupations

The arts of painting and sculpture

Home & retirement

Better get down to storyboarding and arranging locations and interviews… If you'd like to be one of my subject experts - please email me.

* For sat down/sitting down and thinking, please read "lying on my back, eyes half-closed, mouth half-open with a small trail of dribble sparkling across my cheek". Essential part of the creative process, innit…